Why are kids’ eyes growing too big?

Shortsightedness isn't inevitable - there are many ways to help your kids' eyes grow normally

Lake Malawi lapped gently against the rocks on the shore. There were other people having a good time inside the bar, but I couldn't relax. Sweat was running down my forehead and stinging my eyes. Tall thunderclouds were feeding on the oppressive humidity, and I couldn't even take a deep breath for fear of inhaling the fluttering lake flies that were dropping onto my makeshift table in their hundreds.

Growing tired of squinting through the fog of (apparently entirely edible) insects, I looked away from the lake and noticed one of the women near me was reading an Agatha Christie and my eyes lit up. I can never resist some Golden-Age detective fiction, and it was clear that we'd have something in common. As our conversation drifted from authors to learning to read to wide-ranging children's literature, I became more and more curious. “This is a strange question, but how is your vision?”

Eye growth is started by our genes and tuned by our environment

Humans are phenomenally visual animals. Almost the entire back half of our brains are dedicated to processing visual information. Our incredibly complex eyes bend the right amount of light to the right part of the retina, where it smashes into opaque proteins that convert the light energy to electricity and trigger nerve cells. After a bit of in-eye processing (texture and contrast enhancement, edge-finding, colour compression, etc.) the image is then shipped to the back of the brain down the optic nerves, where it's patched up with memories of the virtual model of our surroundings before being presented to the consciousness.

During development, our genes drive the eye’s construction from just proteins, water, various oils and a pinch of salt. After we’re born, all we have to do is tune those eyes so that they start working properly; and then maintain them so they keep working properly.

The initial tuning process of the eye involves:

Training the image-processing parts of the brain to recognise shapes, textures, etc.

Enhancing the eye-moving muscles and reflexes

Growing the eyeball into the right shape so the image comes to focus exactly on the retina.

While all of those parts can go wrong in various contexts, the last one is the most common: long-term autofocus (or emmetropisation if you want more syllables) .

The eyes of new-born babies are all long-sighted, and to grow into the right shape, there's a band of cells around the middle of the eye that should grow until images are in focus and then stop. But in many children, including the one that would grow up into me, they don't stop. This means that our eyes grow too long, light from further objects focuses in front of the retina, and we can only see things that are very close. I had to memorise the colours of my friends’ swimming costumes when we went to the pool, because there was no chance I’d be able to recognise their faces.

When eyes aren’t properly tuned by the environment, we get vision problems

Shortsightedness, or myopia, has increased catastrophically in the last few generations. In some places we're up to more than 75% of the population and still increasing. It is, by far, the most common visual defect.

When I first heard about the “Myopia Epidemic” I imagined that it meant some profit for contact lens manufacturers and not much else. I was very wrong.

Being a poorly-vascularized, unsupported, hollow ball of an organ, the eye relies heavily on pressure to maintain its overall shape, ensure the right amount of nutrients and oxygen reach its tissues, and hold some of its parts in place. This pressure is maintained by some cells near the lens that produce fluid, and a little escape valve (with the excellent name of ‘The Canal of Schlemm’) that lets this fluid escape from the eye into the blood.

Change the shape of the eyeball and you change the shape of the escape valve, which means you change the pressure within the eye, which eventually means you mess with how the entire eye works. People with long eyeballs (i.e. myopia) are much more likely to suffer retinal detachment, glaucoma (including optic nerve damage), and cataracts. We're not just facing an epidemic of contact lenses, we're going to experience an epidemic of blindness. We really should think about this more deeply:

What should stop our eyes growing? And why doesn't it?

Close-focus work in dim light provides the wrong environmental inputs

That is still up for debate, but I can tell you what we know:

The eye overgrowth is in direct response to reduced oxygen in parts of the white of the eye (the ‘sclera’).

These parts of the sclera are deprived of oxygen when the blood vessels running to them are narrowed by tension.

These three things load tension into the sclera:

the muscles that winch the iris open in dim environments, or when you're really concentrating;

the muscles that pull the lens into shape for closer focus;

the muscles that reposition the eyeballs to point at nearby things instead of being parallel.

And those three things are done for long, long periods by kids put through hours inside writing or reading at school and then hours inside with phones or books at home.

Alongside this there may be other effects based on defocused images forming on the retina, circadian rhythm disturbance worsened by blue light, and even possible effects from abnormal face shape caused by lack of chewing, but the evidence is clear: long periods of close-focus work, especially in the dim light indoors, cause shortsightedness.

Biting off less than we can chew

Face shape affects eyesight. And not in a good way. In a ‘vicious cycle’ sort of way: there's a suggestion that under-growth of the upper jaw reduces the height of the lip at the bottom of the eye socket, which, in turn, reduces the back pressure on the eyeball, worsening any myopia that's occurring. It would be a small effect, but a gentle push towards a box marked ‘Epidemic of Blindness - Do Not Open’ is no good thing.

All of which I was thinking of while talking to a woman in Malawi who’d read Agatha Christie (and, I assume, other things) for hours every day since childhood, but had always had perfect eyesight. Hey! I thought. That’s not fair! We both ploughed through cubic metres of novels as children and my eyes suffered and yours didn’t. Why?

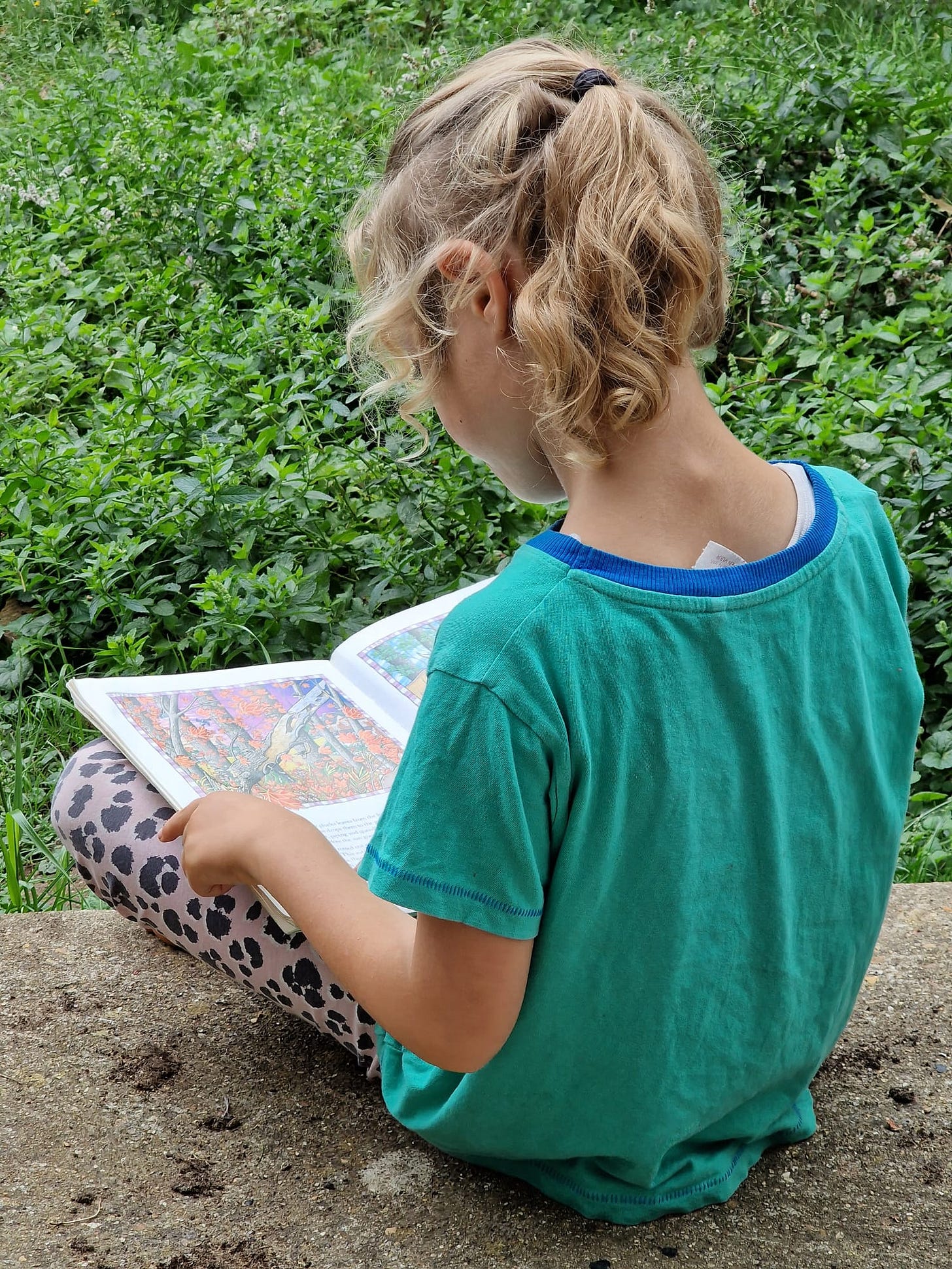

The thing I realised is, other than health being a game of chance, is that it wasn't books that damaged my eyes, it was how I read them. She had grown up near a rare school library and, like me, exploited it voraciously. However, without electric light at night, and it being too hot to stay inside during the day, she'd devoured her books at arm’s length outside under a tree, frequently glancing away at her environment, friends, nearby chickens, etc.. As an adult, her eyesight is perfect. I read my books with a torch, hiding under the duvet when I was meant to be asleep. My eyes worked incredibly hard, without a break, and it messed with their development. Same action, different methods, different long-term results.

But there are a few simple ways that we can reduce the risk of shortsightedness

So, how can we use this science to help our children have better eyesight than we do?

Aim for at least two hours a day outside. Schools, there’s plenty of evidence on how a lesson outside a day can drastically slow the myopic progression of your students. Parents - it doesn’t have to be much, and doesn’t have to be all at once. What works at getting your kids outdoors? I’d love to hear your tried-and-tested ways to get kids outside!

Read books or use tablets outside or, if that’s not possible, right next to the window. Think how to set up the environment to encourage this. What does your kid really want? A heater? A beanbag? A place to curl up next to the dog’s bed?

Keep books out of the bedroom. When they're young, tell them stories without showing them the book. When they're older, audio books. (As an aside, when I first learnt this, I was very sad. I loved reading in bed, and I worried that depriving her of that guilty pleasure would spoil her enthusiasm for books. I needn’t have worried. She devours them as voraciously as I ever did - but downstairs, outside, in the sunshine).

If you’re really interested in the research behind how eyes develop and want some more tips and tricks for maintaining eyesight, I’ve put some more detail in my upcoming book ‘Growing up WEIRD’. Just, please, do it at arms’ length, somewhere brightly lit, and preferably with nearby chickens!

You may also like:

Prefer a podcast?

Notes

Good overview of emmetropisation here: Flitcroft, D. I. "Emmetropisation and the aetiology of refractive errors." Eye 28.2 (2014): 169-179.

A terrifying glimpse into the future eye problems of us myopics here: Williams, Katie, and Christopher Hammond. "High myopia and its risks." Community eye health 32.105 (2019): 5.

Hypoxia drives myopia here: Zhao, Fei, et al. "Scleral HIF-1α is a prominent regulatory candidate for genetic and environmental interactions in human myopia pathogenesis." EBioMedicine 57 (2020).

Scleral blood vessel tension and hypoxia here: Wu, Hao, et al. "Scleral hypoxia is a target for myopia control." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115.30 (2018): E7091-E7100.

Other factors that contribute to myopia here: Grzybowski, Andrzej, et al. "A review on the epidemiology of myopia in school children worldwide." BMC ophthalmology 20 (2020): 1-11.

Link between crooked teeth and myopia here: Grippaudo, Cristina, et al. "Bite and sight: is there a correlation? Clinical association between dental malocclusion and visual disturbances in pediatric patients." Applied Sciences 10.17 (2020): 5913.

School interventions to reduce myopia progression example here: Jiang, Dan-Dan, et al. "Elementary school comprehensive intervention and myopia development: the Wenzhou Epidemiology of Refraction Error Study." International Journal of Ophthalmology 15.8 (2022): 1363.

very interesting. How do you think this plays into the debate about when is the best age to teach children to read. Or, maybe it doesn't matter, as long as you teach them to read outside?

Anecdotally, I read a lot outside and also read in my bedroom simply by the light of the moon 😂 which is probably much worse than using a flashlight. I’m in my late 20s and don’t have vision issues! When I was in grad school I wore some prescribed readers for fatigue, but I haven’t worn them much since, and I read about 2-4 books a month. So I think as long as your kids are getting lots of sunlight and time outside, letting them have the occasional night time reading binge is probably not going to mess up their eyes. We had a hammock and I would read there — it was great motivation for me to lay in that while reading outside!